# init repo notebook

!git clone https://github.com/rramosp/ppdl.git > /dev/null 2> /dev/null

!mv -n ppdl/content/init.py ppdl/content/local . 2> /dev/null

!pip install -r ppdl/content/requirements.txt > /dev/null

Bayes theorem continuous#

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

from scipy.integrate import quad

from rlxutils import subplots, copy_func

from progressbar import progressbar as pbar

%matplotlib inline

def get_posterior(likelihood_fn, prior_fn, support, atol=1e-5, integration_intervals=1000):

assert len(support)==2

xr = np.linspace(*support, integration_intervals)

Z = np.sum([likelihood_fn(x)*prior_fn(x) for x in xr]) * (xr[1]-xr[0])

posterior_fn = lambda x: copy_func(likelihood_fn)(x) * copy_func(prior_fn)(x) / Z

return posterior_fn

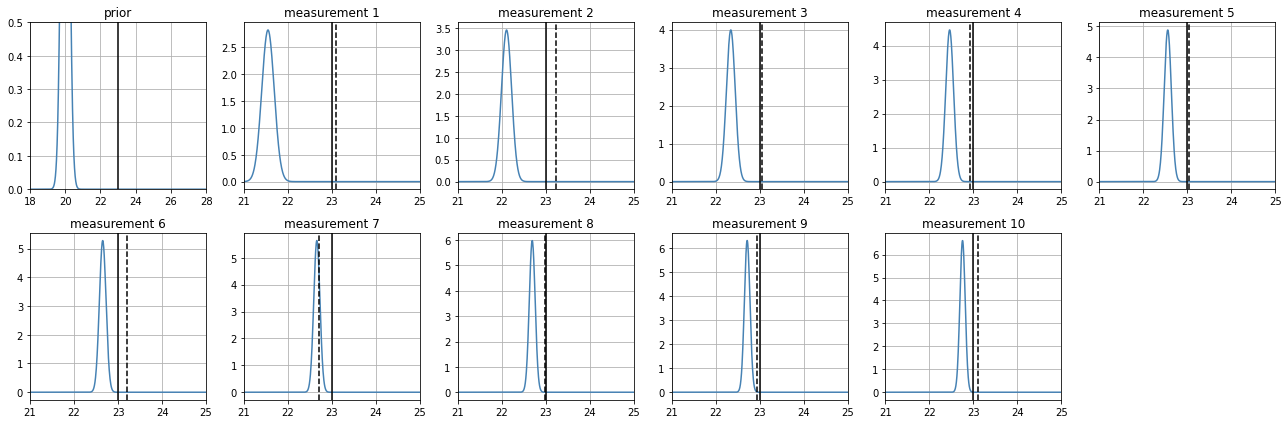

the posterior of one measurement#

support = [-20,20]

likelihood = lambda x: stats.norm(loc=2,scale=.5).pdf(x)

prior = lambda x: stats.norm(loc=4,scale=1).pdf(x)

posterior = get_posterior(likelihood, prior, support)

xr = np.linspace(*support,1000)

plt.plot(xr, likelihood(xr), label="likelihood")

plt.plot(xr, prior(xr), label="prior", color="black", lw=1)

plt.plot(xr, posterior(xr), label="posterior", color="black", lw=4)

plt.grid();

plt.legend();

plt.xlim(0,5);

several measurements#

we repeat the steps above, using the posterior obtained at each step as the prior for next measurement

def estimate_position(

z_real = 23,

prior_mean = 20,

prior_std = 10,

sensor_sigma = .7,

support = [-10, 50]

):

initial_prior = eval(f"lambda x: stats.norm(loc={prior_mean},scale={prior_std}).pdf(x)")

measurements = np.random.normal(loc=z_real, scale=sensor_sigma, size=10)

posteriors = []

prior = initial_prior

for i in pbar(range(len(measurements))):

# compute the likelihood

likelihood = eval(f"lambda x: stats.norm(loc={measurements[i]},scale={sensor_sigma}).pdf(x)")

# compute the posterior, stop if integration errors

posterior = get_posterior(likelihood, prior, support)

posteriors.append(posterior)

# the posterior becomes the next prior

prior = posteriors[-1]

# plot stuff

xr = np.linspace(*support, 10000)

for ax,i in subplots(len(posteriors)+1, n_cols=6):

if i==0:

plt.plot(xr, initial_prior(xr), color="steelblue")

plt.title("prior")

plt.ylim(0,0.5)

plt.xlim(z_real-5, z_real+5)

else:

plt.plot(xr, posteriors[i-1](xr), color="steelblue")

plt.title(f"measurement {i}")

plt.axvline(measurements[i-1], color="black", ls="--")

plt.xlim(z_real-2, z_real+2)

plt.grid();

plt.axvline(z_real, color="black")

plt.tight_layout()

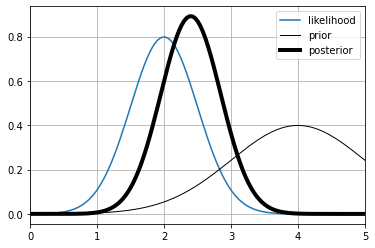

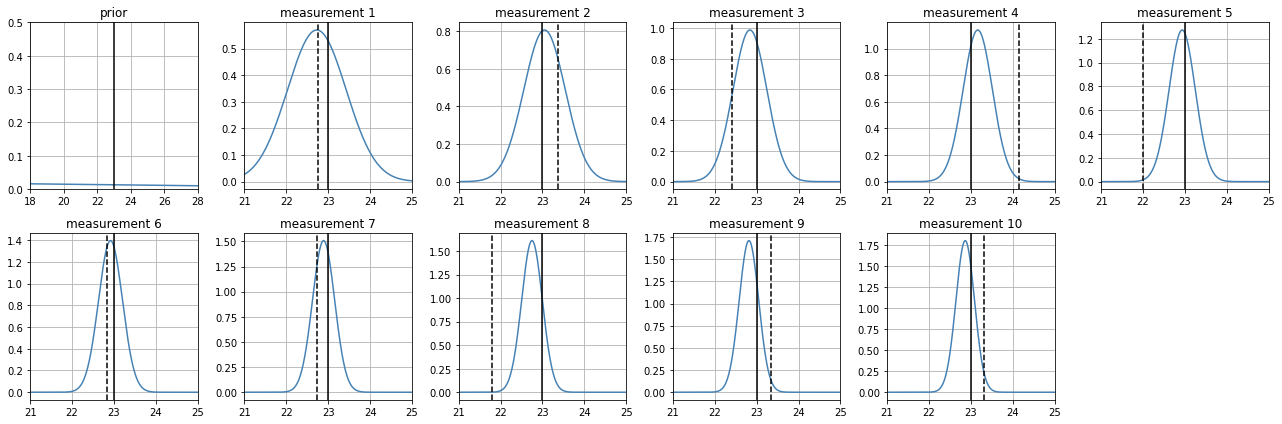

a very uninformative prior#

observe how, as measurements are processed, the posterior becomes narrower (less uncertainty) and approaches the real value

estimate_position(

z_real = 23,

prior_mean = 5,

prior_std = 20,

sensor_sigma = .7

)

100% (10 of 10) |########################| Elapsed Time: 0:00:27 Time: 0:00:27

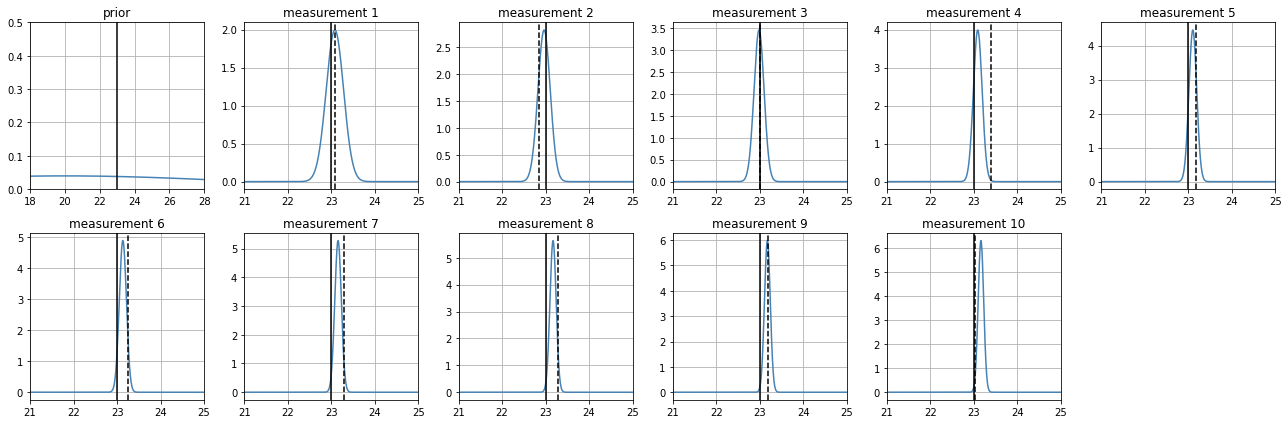

a more accurate sensor converges faster and with less ucertainty#

however observe that numerical integration might stop us from processing further measurements

estimate_position(

z_real = 23,

prior_mean = 20,

prior_std = 10,

sensor_sigma = .2

)

100% (10 of 10) |########################| Elapsed Time: 0:00:28 Time: 0:00:28

but if we are very wrong and very confident on our prior, we pay for it#

Wrong mean with a very narrow stdev. It takes many measurements to converge to the real value.

Recall, narrow stdevs anywhere always represent small uncertainty

estimate_position(

z_real = 23,

prior_mean = 20,

prior_std = .2,

sensor_sigma = .2

)

100% (10 of 10) |########################| Elapsed Time: 0:00:28 Time: 0:00:28